The Japanese Occupation was one of the darkest memories history has left with Singaporeans. Many of us have grandparents or relatives that bore witness to the brutal Sook Ching campaigns, where the Japanese military police (kempeitai) massacred thousands of innocent Chinese. Every 15th of February (Total Defence Day) we are – rightly – reminded that we need to defend our nation against such atrocities to make sure they never happen again.

And yet, every dark age of history produces men and women who show that the human spirit crosses all ethnic and national lines. During the Holocaust, one such individual was Oskar Schindler, a German who saved the lives of 1200 Jews and was the subject of the classic film Schindler’s List (1993). Such heroes existed right here in Singapore during World War II. The deeds of Shinozaki Mamoru (born 1908, died 1990) were never made into a movie, even though he saved the lives of more than 2000 Chinese and Eurasians. Here is his story.

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Even before they landed on Singaporean shores, the Japanese had planned out a near-genocidal operation to exterminate ‘undesirable’ Chinese in Singapore. Japanese-Chinese animosity was at its peak, because the Japanese then controlled much of China. From 1942 to 1945, thousands of young Chinese men were rounded up and brought to kempeitai screening centres at the YMCA Building in Stamford Road and the Central Police Station in the Chinatown district. The lift of a finger from masked kempeitai informants could mean the difference between life and death for many of the Chinese youths picked out at random by the Japanese military. A few were triad members, anti-Japanese agitators or Communists. Most were clueless young men, who might have been tortured and bayoneted simply for not grovelling properly to a passing Japanese officer.

Shinozaki had been jailed by the British for spying before the Occupation, but was released by the Japanese and hailed a hero. As Advisor to the Defence Headquarters, he would have witnessed kempeitai torturers at work. Infamously, they would force a prisoner to drink water from a high-pressure hose before kicking his stomach with their leather boots. Such cruel tortures were too much for him to bear. As Advisor, he issued thousands of ‘good citizen’ and safe-passage passes to Chinese, Eurasians and foreigners alike. These were only supposed to be issued to Japanese collaborators and foreign diplomats, but Shinozaki issued almost 30000 of them. By his own estimation, around 2000 Chinese were saved from Japanese concentration camps alone. He also helped the starving by ensuring that a charity home run by the Catholic Little Sisters of the Poor had a steady supply of food.

Shinozaki also rescued many prominent members of the Chinese community – who had served as philanthropists and community leaders. Among them was Dr. Lim Boon Keng – the founder of the Overseas Chinese Banking Corporation (OCBC). These leaders then formed an Overseas Chinese Association (OCA) at Shinozaki’s suggestion. Admittedly, there is a dark side to this. The OCA was later forced to make a $50 million ‘donation’ to the Japanese government. When it was unable to meet this amount, it was forced to borrow from Japanese banks. However, historical evidence suggests that this happened only after Shinozaki was removed as OCA Advisor, having made enemies after his pro-Chinese activities. The OCA was placed under military control and Shinozaki fled to Japan to avoid a court martial.

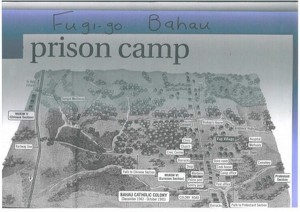

Two months later in 1942, Shinozaki returned as Chief Welfare Officer with the OCA, now under civillian control once more. He next helped re-settle over 12000 Chinese and 3000 Eurasians in Endau and Bahau respectively. These farming settlements in Malaysia were supposed to enable them to grow their own food and avoid starvation. Malnutrition and disease were by then rampant in Singapore because the Japanese Army had taken control of most food supplies. Shinozaki served as the only liason between the villagers and the Japanese government.

Bahau Settlement, c. 1943. Photo Credit: http://chinesecommunity.org.nz

Unfortunately, life in the settlements was hard. Many Singaporeans including Catholic Bishop Adrien Devals died of malaria and tetanus. Nonetheless, Shinozaki played a key role in making life better for the settlers. To stop raids on Bahau and Endau by the Communist Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) guerillas, he bribed them with bags of rice. For this treasonous action he would likely have been court-martialed and executed.

After the Japanese surrender in 1945, Shinozaki was captured and imprisoned along with over 6800 Japanese. However, the Chinese and Catholic communities petitioned for his release. He was in fact set free and later worked translating kempetai reports on MPAJA guerillas for British intelligence.

More significantly, he was a prosecution witness during war crimes trials in Singapore. In this role, he also helped prevent the conviction of community leaders such as Charles Paglar. Paglar was accused of treason for serving as president of the Japanese-controlled Eurasian Welfare Association and publicly supporting the emperor. This was even though he had provided free medical services to members of his community and risked his life carrying medicine to the Endau settlement through guerilla-controlled territory.

Admittedly, much of our knowledge of Shinozaki’s actions comes from his memoir – Syonan: My Story. However, his heroic deeds have also been corroborated by Yap Pheng Geck, a Captain in the Chinese Volunteer Corps. The memoirs of John van Cuylenberg, a Eurasian doctor, also corroborate his account. Add to this the fact that Chinese and Catholic leaders specifically asked the British for his release, and we can be fairly sure that history has recorded his heroism correctly.

History may have recorded Shinozaki’s actions correctly, but it has largely forgotten him. No where is he to be found in the Social Studies and History textbooks of our schools, and he remains very much a figure known only to scholars and professors. That is a pity, for we should never forget that the human spirit always blurs simple lines of conqueror and conquered, oppressor and oppressed.